Yoga Poses That can Cause Shoulder Impingement

Yoga poses where shoulder impingement can be a problem include

- Arms overhead poses like Warrior 1,

- Arms at shoulder height like Warrior 2,

- and poses where the arms support some or all of the weight of the body (with the arms past the head) as in Downward Dog, Handstand, Bound Headstand and Forearm Stand.

Weight Lifting Exercises That can Cause Shoulder Impingement

Weight lifting actions where shoulder impingement can be a problem include

- Military Presses,

- Upright Rows,

- Forward Dumbell Raises (with palms facing down) and

- Lateral Dumbell Raises (again with palms facing down.

With the latter two exercises, a simple way to avoid shoulder impingement is to do them with palms facing inwards (forwards in the case of lateral raises) or even upwards.

With the military press a simple fix may be to do it one arm at a time with a dumbell but side bend your spine away from the lifting side to help give your lifting shoulder clearance. Turning the palm inwards may help also.

Preventing Shoulder Impingement

How do you get around the possibility of shoulder impingement?

By learning to feel (and control) your shoulders so that you can notice when impingement occurs and so that you can then work at preventing should impingement.

The idea here isn't to say that you avoid exercises that can cause shoulder impingement. Instead you learn to do the exercises in such a way that you don't cause it. And that means learning to feel and control your shoulders and the structures that affect them.

If you can feel your body and you still can't figure out how to avoid impingement in a particular exercise, then leave the particular exercise or pose out.

The Shoulder Girdle, Cervical Spine and Ribcage

The shoulder blades and collarbones form the shoulder girdle. This in turn rests on the ribcage like a bony shawl. The only point of direct bony attachment between the ribcage and shoulder girdle is between the collar bones and the sternum.

Part of dealing effectively with shoulder impingement is learning to feel your ribcage as well as your shoulder girdle (collar bones and shoulders blades.)

Some of the muscles that work on the shoulder girdle attach to the cervical spine and base of your skull. So as well as learning to feel and control your ribcage, you can help avoid shoulder impingement by also developing more awareness and control of your neck and skull

Creating a Foundation for Movement

Since the muscles that control the shoulder blades and collar bones originate from the ribcage and spine, a first step in avoiding shoulder impingement is to make sure that your neck and ribcage offer a stable foundation for the muscles that work on the shoulder girdle. As well as giving these muscles a firm foundation you also have to give them room to move, room to activate.

Building a tall building, the first floor serves as the foundation for the second floor and so on. With the shoulders, the ribcage and spine help to support the shoulder girdle. In turn the shoulder girdle can then acts as a foundation for the muscles that act from there on the arm bones. This is a very simplistic view, but never the less, it's a good and actionable starting point. To avoid impingement in any pose or exercise, make sure that your spine and ribcage are stable, that your scapular stabilizers have room to contract, and that your shoulder muscles also have a stable foundation and room to contract.

Different Groups of Muscles

The muscles of concern, at least as a first level approach, include

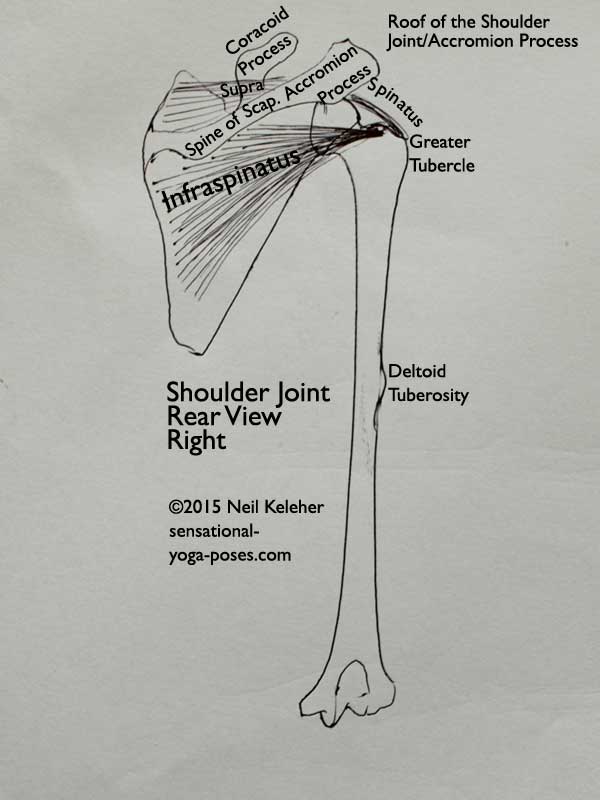

- the muscles that act between the spine/ribcage/head and the shoulder blades.

- Also important are the muscles that attach the shoulder blades to the upper (and lower) arm bones.

- Then there are muscles that attach from the arm bones to the ribcage and spine (and even extend as far at the pelvis.)

The better you can feel your shoulders and the structures and muscles that attach to them and support them, the better you can feel and control the muscles that work between these structures, the better you can work at overcoming shoulder impingement.

I should point out here that muscles not only help to create movement (or stability), they also create sensation when they activate. Those sensations, whether tension in connective tissue, or sensations generated directly within the belly of a muscle, are what you can learn to feel to get a better sense of what is happening when doing yoga or weight lifting or any other activity.

Using Proprioception to Prevent Shoulder Impingement

Part of preventing shoulder impingement includes learning to feel your shoulder blades and the muscles that act on them, so that you can operate them in such a way that you avoid impingement. At the same time you'll be training your brain to operate your body in such a way that it automatically acts in a way that doesn't cause impingement.

Less that Ideal Instruction

One of the possible lead ups to shoulder impingement is improper exercise instruction.

In yoga, one possibly problematic instruction or cue is: pull down on the shoulder blades (to create space between the shoulders and the ears).

This instruction might have actually started of as "pull down on the inner edges of the shoulder blades".

If you create a downwards on the inner edges of the shoulder blade, that can activate the lower fibers of the trapezius which then rotates the bottom of the shoulder blades outwards and the top inwards helping to move the acromion process out of the way of the upper arms as the arms are lifted.

However, that instruction may work best only if the shoulders are lifted (and/or protracted) to begin with.

Lift Your Shoulders to avoid shoulder impingement

A basic instruction to avoid impingement is to lift the shoulders when lifting the arms.

The higher you lift them, the more they rotate inwards and the less likely that impingement is to occur.

And that is in part due to the way that the collar bones and shoulder blades attach to each other, at the inside edge of the acromion process.

As well as lifting your shoulders, you may find it helpful to protract your shoulder blades. Protraction, if you protract far enough, tends to rotate the shoulder socket upwards, in part because of the way the collar bones push out against the accromion process the more the shoulders are protracted.

One possible sequence is to protract the shoulder blades and then lift them. If moving the arms, you could reach the arms forwards as the shoulders are protracted, and then reach them up as you lift the shoulder blades higher.

The Acromion Process is the Highest Point of the Shoulder Blades

Acromion is Greek for highest, which is appropriate since the acromion process is the highest point of the shoulder blades.

Where the outer end of the collar bones attach to the Acromion process, the other end attaches to the top of the sternum. So the distance between the acromion process and the top of the sternum is a fixed constant.

(If you don't really want to read a long ass article, part of the point of what follows is to learn to feel your accromions, not just with your fingers, but with your mind. )

The Movements of the Acromion Process

Forgetting about the arms for a moment and just looking at movements of the shoulder blades relative to the ribcage and the sternum, the shoulder blades and collar bones sit on top of the ribcage like a collar or girdle.

- As you move your shoulder rearwards, the shoulder blades more inwards. The acromion processes then move rearwards and inwards (and, as the collar bones have to ride slightly upwards to get over the top of the ribcage, the acromions move slightly upwards aswell).

- Moving the shoulders forwards there's a point where the accromion processes are a maximum possible distance apart. After passing that point, any further forward movement of the shoulders causes the acromion processes to move inwards as well as forwards.

- Lifting the shoulder blades, the higher you lift them the further inwards your acromion processes move.

- With the shoulders lifted, you could move your shoulders forwards or rearwards. In either case the acromion processes will move towards each other.

Shoulder Rotation, Supraverting the Shoulder Socket

What is also important with respect to impingement isn't just the amount that the accromion processes move inwards but the amount that the bottom tip of the shoulder blades move outwards.

Both of these actions together are what can prevent shoulder impingement, and rather that talking about shoulder blade rotation since it can be easy to get confused, it might be clearer if we talk about changes in the angle of the shoulder socket instead.

In this regard we can use supraversion as a name for the movement of the shoulder blades that causes the "eye" of the shoulder socket to look upwards while infraversion is the movement of the shoulder blades that causes a downward movement of the eye of the shoulder socket.

To avoid impingement when lifting the arms, the shoulders blades need to be supraverted.

Ribcage Posture and It's Possible Affect on Shoulder Impingement

The ribcage is a flexible structure, particularly when movements of the thoracic spine and ribs are taken together.

Backbending and forward bending the ribcage change its shape considerably and can also affect the possibility of impingement.

The ribcage can also bend sideways and this is useful in that it can extend the possible range of safe arm movements particularly when focusing on one arm at a time.

So say doing single arm military presses or upright rows, if using one one arm you can bend your ribcage to the opposite side. This movement carries the shoulder blade with it.

Using the floor as a reference, this causes the shoulder blade to supravert relative to the floor and assuming the same general orientation of the arm, creates clearance between accromion process and the upper arm.

Further supraversion relative to the ribcage will still be required but this maximizes the possibility of creating the required amount of space.

For the rest of this discussion we'll assume the ribcage is fixed in a slight backbending action so that the chest is lifted and stable, the neck long and stable. This then gives the muscles that control the scapula a stable foundation from which to work.

In terms of practicing moving the shoulder blades, it helps to be able to distinguish movements of the ribcage from movements of the shoulder.

Supraversion and the Trapezius

A basic idea with muscle control in general is giving muscles room to contract.

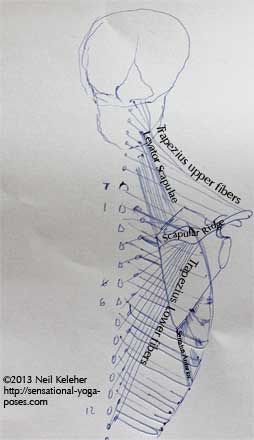

The main muscles that drive supraversion are the three distinct sections of the trapezius.

- The upper trapezius attaches to the outer span of the collarbones and can be used to pull upwards and inwards.

- The middle trapezius attaches to the accromion process and parts of the scapular ridge inwards from there and can be used to pull upwards and inwards (but less upwards than the upper portion).

- The lower portion attaches to the scapular ridge and pulls downwards and inwards.

The trapezius attaches from the shoulder blade to the spine and so to give all three parts of this muscle room to contract it helps to spread the shoulder blades away from the spine and work to keep them spread.

This movement is called protraction and the resultant position can be thought of as the shoulder blades being protracted.

Protraction and the Serratus Anterior

The main muscle that drives protraction is the serratus anterior which wraps from the inner edges of the shoulder blade around the sides of the ribcage to attach to the front corner of the ribcage from rib pairs 1 to 9 (1 being the uppermost pair of ribs).

Like the trapezius the serratus anterior can also be divided into three parts.

Stages of Protraction

Starting with the shoulders in a neutral or relaxed position, protraction of the shoulder blades may initially result in minimal shoulder blade rotation.

Because of the attachment of the collar bone to the sternum, as the point of maximum width for the acromion processes is passes, the acromion processes then move inwards so that as the shoulder blades are protracted beyond this point the upper part moves inwards while the lower points move outwards causing supraversion.

And so the point here is that protraction can be used to cause supraversion.

And so one way to work to prevent shoulder blade impingement is to practice maximizing protraction.

Making the Arms Feel Long

If you have your arms reaching forwards and then protract your shoulder blades the feeling can be like you are lengthening your arms.

What actually happens is that as your shoulder blades protract they also move forwards so that your shoulders move forwards relative to your ribcage.

And so one way you can practice protraction is to protract as you reach your arms forwards. You could start by protracting and then follow with reaching your arms forwards. Then work at sequencing the actions. It can feel like initiating a protraction swings the arms forwards, you catch the swing of the arms and carry it on so that the arms "naturally" reach forwards.

Another option is to reach the arms forwards, keep them there and then protract.

Moving Beyond the Serratus Anterior to Prevent Shoulder Impingement

Because the serratus anterior attach only to the ribs, the higher you lift your shoulder blades the less effective the serratus are at maintaining protraction. Also, with the shoulder blades fully protracted, the outer tips of the collar bones are maximally forwards. And so from this point, as you lift your shoulders higher, the outer tips of the collar bones (and accrommion processes) naturally move inwards as well as upwards.

Maintaining protractive effort of the serratus anterior, the lower points of the shoulder blades may still pull outwards relative to the accrommion processes so that supraversion is created if the shoulder blades are continually protracted as they are lifted.

What creates the lift of the shoulder blades? Assuming an upright position, the upper and middle trapezius. Working against the serratus, but with a slightl offset of forces, they pull inwards on the outer end of the collarbones and the accromions resulting in supraversion. In addition, the lower portion of the trapezius, pulling down on the inner edge of the scapular ridge further aids supraversion.

At maximum lift of the accromions, the collarbone and shoulder blades are clear of the top of the ribcage. As a result, it can be possible to move the shoulder blades rearwards at the top.

Using The Lower Trapezius

As the outer tips of the collar bones move rearwards with the acromion processes, the acromion process move inwards. Because the lower trapezius has lots of room to contract, since the shoulder blades are lifted, then an extra downwards pull by the lower trapezius can be exerted to maintain supraversion.

So far then to avoid impingment when lifting the arms, start with protraction, then lift the shoulder blades while maintaining protraction. At the top you can also retract while keeping lift but while pulling down on the inner edges.

Retracting with the Arms Lifted

A simple action can then be to protract and reach the arms forwards, then lift the shoulder blades (keeping the protraction) and then lift the arms up, then if you like, retract the shoulder blades while keeping the lift and moving the arms back.

If the arms are rotationally stable in the lifted position it can be possible to use the teres minor and infraspinatus to further supravert the shoulder blades.

Down Dog and Preventing Shoulder Impingement

Moving into downward dog, a possible way to train to prevent impingement is to start of in cat pose. Protract the shoulder blades (so that the ribcage moves up, away from the floor) and then keep the protraction as you push the ribcage back.

In downward dog, you keep the shoulder and spine aligned and then relax the shoulder so that your ribcage moves towards your hands and then use your shoulders to push your ribcage back away from your hands.

With the arms overhead, rotation of the upper arms inwards can bring the "bump" of the upper arm closer to the accromion process. If the arms are rotationally neutral, this bump is towards the outside.

Inward rotation (where the biceps side of the arm moves inwards) can rotate this bump towards the accromion process.

Preventing Impingement with Arms Lifted But Elbows Bent

With the elbows bent and the hands clasped behind the head in bound headstand, the upper arms are angled forwards. The Shoulders need to be active in headstand to push the elbows into the floor to help keep balance. To push the elbows into the floor the seratus has to act to protract the shoulder blades. So protraction along with "lifting" helps to prevent or reduce the risk of impingement.

In forearm stand the head is actually lifted. To lift the head the shoulder blades are further up relative to the body. The upper arms are more vertical relative the the torso than they are in bound headstand. If the forearms form a triangle in this position, the bump of the upper arm may come closer to the accromion. However, if lift is maximized, then the shoulder blades are supraverted and so the risks may be minimal. With arms parallel there is even more clearance. In either position, you can accentuate supraversion by using the teres minor, and this may be easier to do with the arms bearing weight because the arms are stabilized in this position by the weight of the body.

Sensing Your Shoulders to Prevent Impingement

Military presses and rows are a hardy exercise to deal with. With arms down in the ready position, you could try protracting and then maintain the protraction while either pressing or rowing.

For rows it may be more important to drop the chest, as well as protract. Dropping the chest may rotate the shoulder blades in such a way that the acromion processes more forwards.

However, rather than taking my word for it, a better approach is to try the action without weight and then with gradually increasing weight, noticing the sensations in the shoulder as you lift and lower.

An exercise that may be helpful as a preparation for rowing is a straight arm forward lift. If you lift with your palm facing down the elbows then point to the sides and you may notice that unless you supravert your shoulders as you lift, you'll be grinding your shoulder (in a bad way.) And so one possible solution is to turn the palms slightly inwards. this rotates the bump of the upper arm downwards if the arms are forwards and horizontal. So you could maintain this angle, or change the angle as you lift.

Another option is with the arm in front and palm angled slighty inwards, protract and supravert the shoulder so that the palm faces downwards.

Note that "sensing your shoulders" while doing any exercise is a little like driving with your eyes open and looking at the road. It allows you to see the edges of the road so that you can stay within them. (Equivalently, so that you can stay on the road or within your lane).

So that "sensing" is less of a chore, work at developing shoulder awareness into a habit so that you do it automatically. And if you then notice that your shoulders hurt (because they are impinging) then change the way you do the exercise, and if that doesn't help, then stop doing it.

I'm guessing that the spurs might be caused by the humerous banging into the root of the shoulder.

And that possibly happens because the upper and mid fibers of the trapezius aren't working properly.

The Upper and Middle Fibers of the Trapezius

The upper trapezius attaches at one end to the rear of the base of the skull and at the other end to the outer end of the collar bone, near where the collar bone attaches to the roof of the shoulder joint.

The middle fibers of the trapezius originate at the back of the upper neck and attach to the roof of the shoulder.

For these muscles to be able to pull up on the outer edge of the shoulder blade effectively it helps if they have a stable foundation. That foundation can be created by lifting the chest and pulling the head rearwards and upwards with the chin down.

It also helps if they have room to move. That room to move is created by the same above two actions, opening the chest and lengthening the neck (by pulling the head up and back.)

The Head, Neck and Chest...

The neck and chest work together and so for alot of movements of the neck it helps to start with the ribcage, in this case lifting the chest and in particular bending the upper portion of the thoracic spine backwards. While the direction of movement is a backwards bend, since the upper thoracic spine tends to curve forwards, this movement acts to straigthen the thoracic spine (or make it straighter.)

The cervical spine, the part of the spine that joints ribcage to head, tends to straighten also as a result.

Straightening the cervical spine increases the distance between the head and ribcage. This creates some length in the trapesius muscle, assuming the shoulder blade is down. Then when the arms are lifted, the trapezius can act to pull up on the outer edge of the shoulder blade, lifting and angling the roof of the shoulder so that the upper arm bone doesn't impinge as it is lifted.

Now is having a "lengthened neck" and open chest a guarantee that the outer fibers of the trapezius will activate when the arm is lifted?

I don't know.

And that's why in my classes I teach a exercise specifically designed to activate these fibers. It isn't so much the exercise as where the awareness is focused while doing this exercise.

Just remember, if you want to avoid shoulder impingement syndrome then use the upper fibers of the trapezius muscle to move the outer edge of the shoulder blade upwards (more so than the inner edge.)

Published: 2017 06 26