How anatomy can be an important part of learning the language of your body

This article was actually inspired by an article called "Learning the Language of the Body by Fanny Tulloch.

In Fanny's article she suggests that learning anatomy isn't that important, that the layman doesn't need to know where the triceps connects in order to use it. And maybe you don't need to know either, unless you are having problems with it or a related part.

But if you want to learn your body well, then I'd suggest that anatomy is, if not an essential part of learning your body, an important part.

A path to learning inspired by injury

My path to learning the body has been peppered with injury. I'm not saying that learning my body has caused injury (except in one case). Rather, learning my body has resulted from me trying to fix my body myself. And that includes dealing with knee pain, hip pain, poor posture, back pain and restricted shoulder mobility.

In addition, when it comes down to improving flexibility, a lack of which could be viewed as a problem, it is understanding anatomy that has helped me to figure out how to improve my flexibility.

In all cases, I've had to learn to feel and control my anatomy as a stage in learning to fix my body.

Anatomy offered a road map of sorts.

Feeling the anatomy of your own body

When I talk of anatomy, I'm not talking about learning the names of attachment points and sounding scientific. And I'm not talking about learning and using the anatomical position.

When I talk about anatomy it's in the context of feeling the anatomy of your own body. And so a better word would be biomechanics. When learning to feel the anatomy of our own body, anatomy texts offer a valuable guide to mapping our own body.

Since muscles are the generators that create sensation, the better you can feel muscle, the better you can control them, the easier it is to talk with your body.

Muscles generate sensation

What happens when a muscle activates? It creates a strong sensation within itself (the belly of the muscle). Tense a bicep, and you can feel the sensation of muscle activation. Likewise if you pop your pecs or squeeze (activate) your buttocks. The sensation an activated biceps creates generally occurs within the belly of the bicep. So not only can you feel your biceps activating, you can also feel where it is.

In addition, contracting a muscle generally creates tension in tendons and ligaments. (Yes, ligaments too!) And this is something else that you can feel. For example, tensing your biceps you may notice that the your elbow feels "strong". You can feel the tension in the tendons and ligaments there. So now you can feel your elbow.

If you go the other way, you may notice a pulling sensation near the front of the shoulder. Read a bit of anatomy and you can figure out that probably what you are feeling is the corocoid process.

The two types of sensation that muscles generate

The things that generate tension are muscles. Muscles aren't just force generators. Or rather, the forces that muscles generate aren't just for creating movement or stability. They are also for generating sensation.

Muscle activation creates sensation in the belly of the muscle itself. Anyone who has ever tensed a bicep, popped their pecs or activated their buttocks has felt this type of tension. It also generates sensation by adding tension to connective tissue. And this is a subtler sort of sensation.

The Chinese describe it as Qi because it's the sensation that you can feel when the large muscles and their big bellies are largely quiescent. qi, or connective tissue tension is created by smaller muscles whose bellies are smaller or thinner or less numerous in terms of fascicle count so that sensation from the muscle itself is less obvious.

So muscles, when they activate, don't just create movement or stillness, they also generate sensation.

Not the names of the muscles, but the muscles themselves

If you want to learn how to talk to your body, or listen, anatomy can be a very useful guide. Note that you dont' have to learn names of muscles. Names aren't that important except for when looking up a particular muscle in an anatomy test. What's more important is being able to feel your muscles when they activate and relax.

Reference points

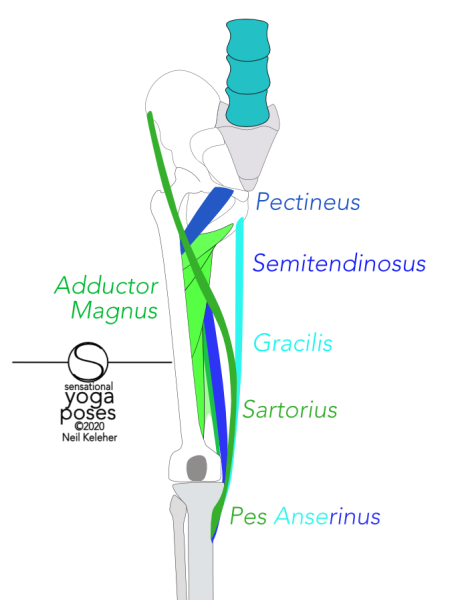

When learning to talk to your body, muscles are important. However, just as important are bones and bony reference points.

I once overheard a massage therapist turned yoga teacher talking about how massage therapists use bony reference points to locate muscle insertions. When investigating and learning our own bodies we can do the same thing. We can use bony references as reference points for pain or sensation and that in turn can help us understand what muscle is being affected. Or we can use bony references as a means of stabilizing the end point of a particular muscle or as a reference for activating a particular muscle.

Your living, breathing body versus a slab of meat on a surgical table

Note that the goal here isn't to learn anatomy for the sake of it, but to get a better understanding of our own body.

To that end, it helps to understand that ligaments are active structures. They are affected by muscle tension just as much as tendons are. Don't forget, we're dealing with a living body, your own body, not a slab of meat that's been dissected and cleaned up.

Understanding ligaments as active structures is important because ligaments tend to attach to joint capsules. (And in some cases, tendons do too.)

Lubrication (not the kind that comes in a jar)

Joint capsules are connective tissue envelopes that help hold the bones of a joint together. In addition they contain synovial fluid. This is generally thought of as lubricating fluid.

To keep bone ends lubricated, it helps if the bone ends are separated. And this is where understanding ligaments as active structures is helpful.

If a muscle is active it in turn adds tension to attached ligaments which in turn add tension to the joint capsule. The affect is much like squeezing a water balloon. The ends where you aren't squeezing bulge outwards. Likewise, adding tension to the joint capsule pressurizes synovial fluid which then acts to press outwards on the bones the joint connects. Thus space is maintained.

By the way, this type of lubrication is called hydrostatic lubrication. In marine engines, this type of lubrication requires a pump to pressurize lubricating fluid to keep it between mating surfaces. If mating surfaces are kept apart, whether in joints or marine engines, less wear and tear results.

The fall back is boundary layer lubrication. This is a type of lubrication that involves frictioning between mating surfaces and wear and tear or the mating parts. Now while our body is a living thing, rely on boundary layer lubrication too excessively and your joints may eventually wear out.

(Another type of lubrication is hydrodynamic lubrication. This relies on the same effect that causes hydroplaning and it occurs when you get high relative speeds between articulating surfaces. That occurs when you move, particularly when you move quickly.)

So why is understanding this important?

The brain is programmed to protect joints

Joints are critical structures. Muscles are important but they have some overlap. And so if a particular muscle isn't working, other muscles can take over so that the joint is protected and mobility, as much as possible, is maintained. Pain or poor performance may be due to your brain limiting movements in order to prevent joints from being operated in dangerous circumstances, i.e. when a joint may be in danger of relying too much on boundary layer lubrication.

If you learn to talk to your body, then by the time your body has healed from an injury, you have the ability to figure out what muscles to activate, how to adjust your positioning so that you can move and control your body effectively. Part of figuring out which muscles to activate can be based on the idea of keeping joints protected (or lubricated).

So why bother learning the language of the body?

Now learning something as complex as your body can be difficult, but only as much as learning worthwhile is difficult. Like anything else, you can break the body down into parts to make learning it a lot easier. Anatomy can be a guide to how you break it down. Why?

If muscles are not just motors, but sensation generators, then learning where your muscles are is a good way to to not only control your body but also to get a feel for it.

The idea of learning the body in this case is so that you can feel and control parts of the body without having to think about how to do it.

If you've learned to drive a car, or better yet, a motorcycle, it's pretty much the same thing, but with a lot more to learn. The nice thing is, that anatomy can help guide you. (And as an added bonus, you can learn anatomy at the same time.)

Published: 2020 04 18

Updated: 2021 01 29